Modern football is too complex, fast, and unpredictable to be controlled through constant instruction. Every moment presents players with new information: shifting defensive lines, changing numerical situations, and evolving spaces. No coach, no matter how detailed, can script every movement or decision in advance.

Traditional coaching often relies on explicit commands — “play wide,” “drop between the lines,” “press now.” While this can create short-term clarity, it often limits adaptability, decision-making, and creativity. Players learn to wait for instructions rather than solve problems themselves.

Self-organization offers a different approach. Instead of prescribing exact actions, coaches design training environments that allow desired behaviours to emerge naturally. The key tool for this is the manipulation of constraints — the rules, spaces, numbers, and incentives that shape how players interact with the game.

For coaches and analysts, the question is no longer “what should I tell players to do?” but rather “how can I design the session so players discover the solution themselves?”

What Self-Organization Looks Like on the Pitch

Self-organization is sometimes misunderstood as freedom without structure, but in football it is closer to guided order. Players are not left alone; they are placed in environments where interaction with teammates, opponents, and space leads them toward effective solutions.

On the pitch, self-organized teams often show:

- Better spacing without constant correction

- More natural synchronization between players

- Faster decision-making under pressure

- Greater adaptability when the opponent changes behaviour

The important detail is that these behaviours are not rehearsed movements. They are responses to cues. Players learn to recognise when to drop, when to stretch the pitch, and when to accelerate play because the environment repeatedly demands it.

Why Heavy Instruction Has Clear Limits

Explicit instruction is not inherently wrong, but it has limits that often show up in matches. When players are coached mainly through commands and corrections, learning becomes externally driven. Players start looking to the sideline for answers instead of finding solutions on the pitch.

Over time, this can lead to slower decisions and rigid play. Patterns might work in training, where conditions are controlled, but break down as soon as the opponent defends differently or removes the expected option. The issue is rarely effort or intelligence; it is a lack of ownership over the decision-making process.

Self-organization addresses this by changing how players learn. Instead of being told the solution, they learn how to search for one.

Constraints: The Quiet Way Coaches Shape Behaviour

Self-organization does not happen by accident. It is guided through constraints — the conditions that shape how players interact with the game.

Constraints can include pitch size, player numbers, scoring rules, directional play, touch limits, or how transitions are organised. Small changes in these elements can have a big effect on behaviour.

For example:

- A narrow pitch naturally encourages central combinations and compactness

- A wider pitch invites stretching the opposition and using the flanks

- Numerical overloads promote scanning and finding the free player

- Numerical inferiority encourages cover, balance, and collective movement

The key point is that the environment teaches. Players adjust because certain solutions work better than others, not because the coach tells them to.

Designing Training That Invites the Right Behaviour

Good training design usually starts with a simple question: what behaviour do I want to see more of on match day? From there, the task is not to explain that behaviour, but to create a game in which it becomes difficult to avoid. If the structure of the drill allows players to succeed without showing the desired behaviour, learning will drift away from the coach’s intention.

This is why the solution to the problem within the drill must be the behaviour the coach wants to train. When players are repeatedly placed in situations where one type of decision consistently leads to success, they begin to organise themselves around that solution without being told to do so.

Making the Environment Teach the Behaviour

Constraints play a central role here. By shaping space, rules, or scoring incentives, coaches can guide behaviour indirectly and far more effectively than through constant correction. The environment begins to reward certain actions and discourage others, allowing players to discover the logic of the behaviour on their own.

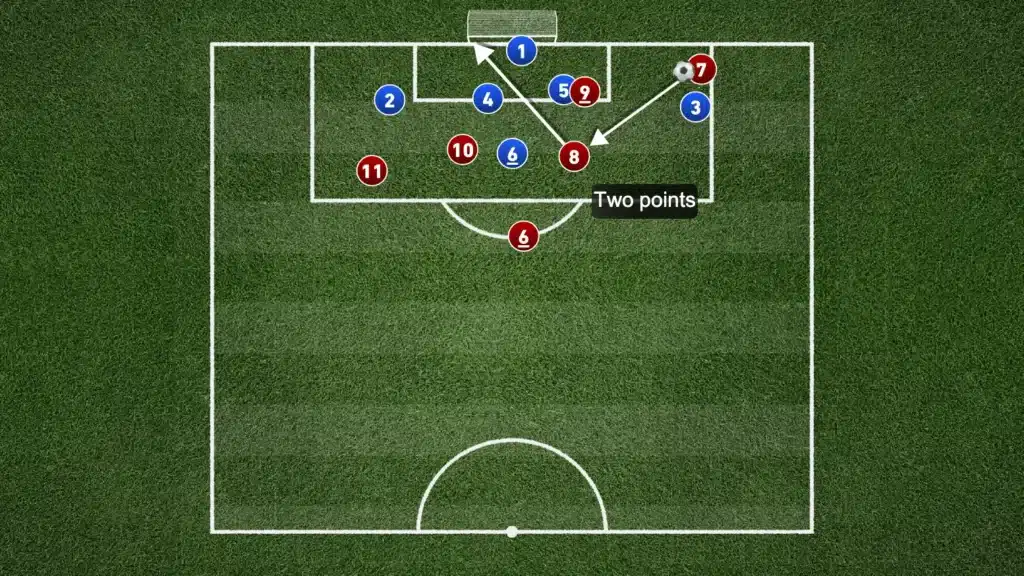

For example, if wingers tend to stay too wide in transition moments and fail to attack central spaces quickly enough, the training environment can be adjusted to promote different movement patterns. In counterattacking drills, cutting the pitch diagonally in the final third naturally funnels wide players inside, making central runs the most efficient way to progress and finish attacks. The winger does not move inside because the coach demands it, but because the space invites it.

Similarly, if the objective is to score more from cut-backs in the final third, the task can be designed to reward that action directly. Awarding extra points for goals scored from cut-backs changes how players approach wide areas, how attackers time their runs, and how midfielders position themselves around the box.

Well-designed tasks reduce the need for constant instruction. When the environment is right, players encounter the same problem repeatedly, explore different solutions, and gradually self-organise around the ones that work best.

What the Coach Does During These Sessions

Encouraging self-organization does not mean doing nothing. It means intervening with care.

Instead of constant correction, coaches guide attention. Questions often work better than answers, especially when they help players reflect on what they saw rather than what they did wrong. Freezing play can also be useful, but only to highlight relationships — distances, angles, and opponent reactions — rather than exact positions.

There are moments when instruction is necessary, but it should support the environment, not replace it. Too much information too early usually shuts learning down rather than accelerating it.

Common Mistakes When Trying to Coach This Way

Coaches often undermine self-organization without meaning to. Some of the most common issues include:

- Adding too many rules at once, which overwhelms players

- Stopping play immediately after every mistake

- Designing games where the desired behaviour is optional

- Removing structure entirely and hoping learning will “just happen”

Self-organization still requires structure. The difference is that the structure sits in the task, not in constant verbal instruction.

Conclusion: Coaching the Environment, Not the Player

Encouraging self-organization requires a shift in mindset. Instead of controlling every movement, coaches focus on controlling the environment in which movements happen. By shaping space, rules, and incentives, they guide players toward effective behaviours without prescribing them.

In a game as fluid and complex as football, this approach develops players who can think, adapt, and solve problems together. The most valuable learning does not come from instruction alone, but from interaction.

The coach’s role is not to provide every answer, but to design situations that ask the right questions — and trust players to find their own solutions.

All images and visuals in this article are made with Once Sport — a powerful and easy-to-use tactical analysis platform. It helps you annotate clips, visualize movements, and create professional analysis videos. Readers of The Football Analyst get 10% off plus one month free with the code TFA10 at checkout.