In modern football, creating and exploiting space is the foundation of effective attacking play. One of the most common — yet tactically complex — ways to do this is through wide overloads. By concentrating multiple players on one side of the pitch, teams can draw opponents out of shape, create numerical superiority, and open up new avenues to progress the ball or attack the penalty area.

While the concept is simple — outnumber the opponent in a specific area — the execution is anything but. The timing of movements, the roles of each player, and how the team uses the resulting space are what separate effective wide overloads from static, predictable possession.

This article explores the tactical mechanics behind wide overloads, the variations used across different systems, and why some of the best coaches in the world — from Pep Guardiola to Mikel Arteta and Xabi Alonso — rely on them as a cornerstone of their attacking structure.

The Tactical Purpose of Wide Overloads

The main objective of a wide overload is to create numerical superiority (e.g., 3v2 or 4v3) on the flanks. This superiority forces the defending team to make difficult decisions: either stay compact centrally and risk being outplayed on the outside, or shift across and leave gaps elsewhere.

By overloading the wing, the attacking team can manipulate the opposition’s defensive block. Once defenders are drawn toward the ball, large spaces tend to appear on the far side or between the lines. The attacking team can then either:

- Combine through the overload to progress down the wing, or

- Use the overload to draw opponents across before switching play into the newly opened space.

Both outcomes serve the same goal — to disorganize the opponent and attack from an advantageous situation.

Common Structures for Wide Overloads

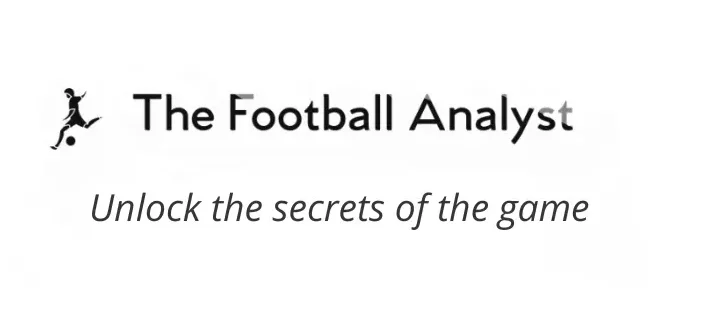

1. Fullback–Winger–Midfielder Triangle

The most traditional form of wide overload involves a triangle between the fullback, winger, and nearby midfielder. This creates multiple passing options at different heights and angles.

- The fullback often provides width or overlaps.

- The winger can hold the touchline or move inside to combine.

- The midfielder offers support inside the half-space to sustain circulation or play third-man combinations.

This triangle structure is common in teams like Barcelona or Liverpool, where positional play principles dictate spacing and rotation between these three players.

2. Inverted Fullback Variations

In some systems, the fullback inverts into midfield during build-up, creating a new type of overload. Rather than forming the triangle on the outside, the overload occurs between the wing and the half-space, allowing more central control.

This setup helps to attract the opposition’s midfielders, creating confusion over who should press — the winger, the fullback, or the interior midfielder. It’s a structure often seen in teams coached by Pep Guardiola or Xabi Alonso, where the inverted fullback becomes a key connector in both wide and central progression.

3. Rotational Overloads

More fluid systems rely on rotations to form temporary overloads. For example, a winger might drift inside, allowing the fullback to push higher, while a striker and an attacking midfielder drop into the channel. This dynamic movement creates constant uncertainty for defenders — who should follow whom?

Fernando Diniz’s Fluminense and Didier Deschamps’s France team have used these types of rotational overloads to great effect, prioritizing movement and timing over fixed positional roles.

The Mechanics of Creating Superiority

To create an effective overload, teams must coordinate both positional and numerical aspects. Having more players near the ball is not enough — they must be positioned to generate functional superiority.

Positional Superiority

Even with equal numbers, an overload can succeed if players occupy better positions. Angles, distances, and body orientation determine whether passing lanes remain open. For instance, a midfielder positioned slightly behind the opposition’s pressing line can receive and drive forward immediately, turning a numerical equality into an effective advantage.

Dynamic Superiority

Timing matters as much as positioning. A well-timed run into the overload area — such as a third-man movement or an overlapping run — can unbalance the defense and create the crucial opening. Teams that move together, rather than simply crowding an area, tend to sustain possession and progress more effectively.

Switching Play from the Overload

A major reason for overloading one side is to create space on the opposite wing. When the opposition shifts their defensive block toward the ball, the far side naturally opens up. Elite teams frequently exploit this by switching play quickly, using long diagonal passes or rapid circulation across the midfield.

This overload-to-isolate principle allows teams to first attract pressure and then attack through isolation on the opposite wing, where a skillful player can take on an exposed fullback 1v1.

Using Overloads to Progress and Penetrate

While some teams use overloads primarily to retain possession, others use them as a launching point for penetrative actions.

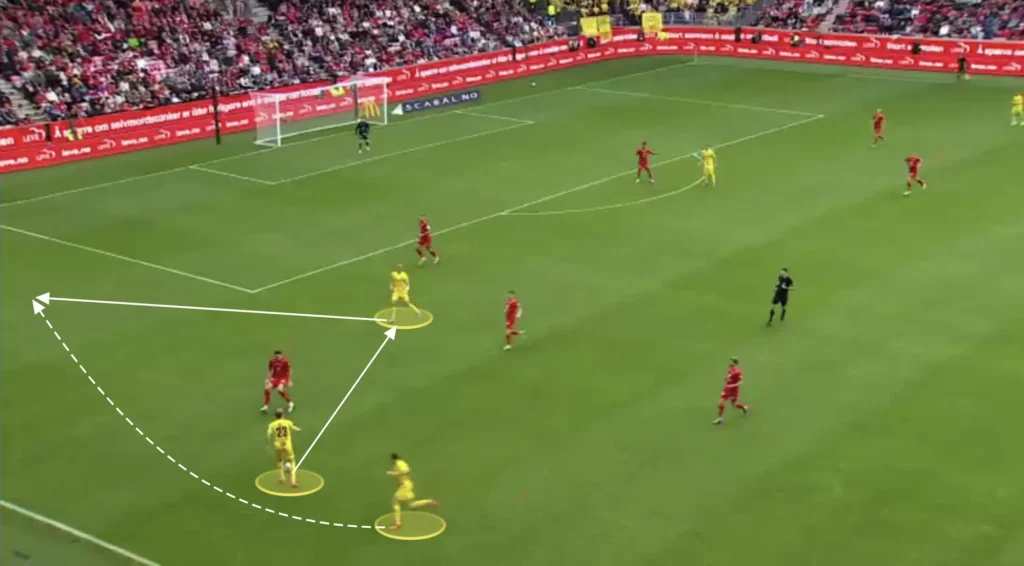

1. Overlaps

When the wide overload pulls the opposition fullback toward the ball, the attacking fullback often makes an overlapping run on the outside. This movement stretches the defensive line horizontally, creating space for a cross or a pass into the channel. It’s especially effective when the winger carries the ball inside, as the overlap offers a wide passing lane and opens the byline for cut-back opportunities.

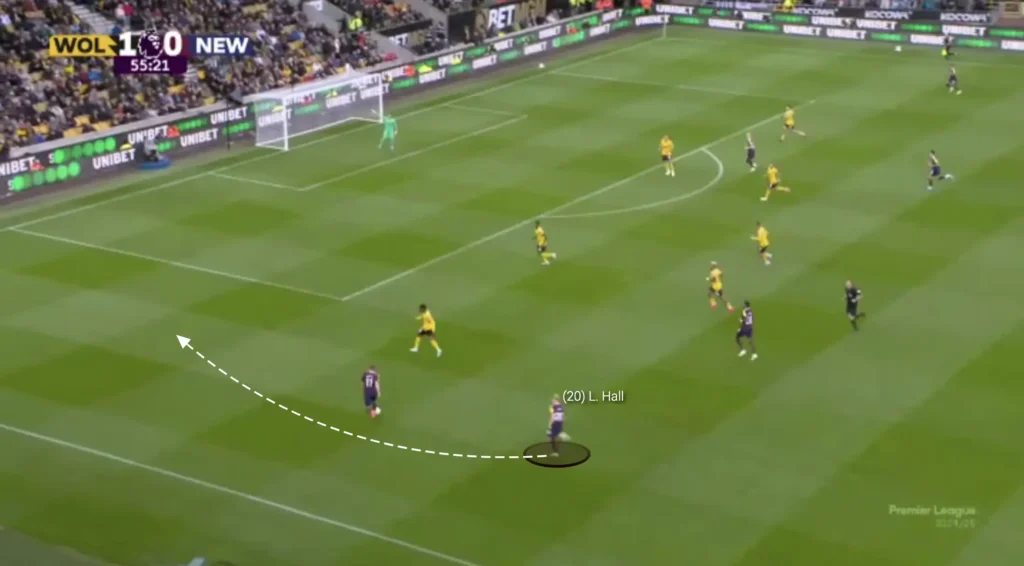

2. Underlaps

Alternatively, the fullback or a nearby midfielder can make an underlapping run, attacking the space between the opposition fullback and center-back. This inside movement disorganizes the backline, forcing defenders to make quick decisions. It can lead to penetrative passes into the box or quick combinations that result in shots or low cut-backs from dangerous central areas.

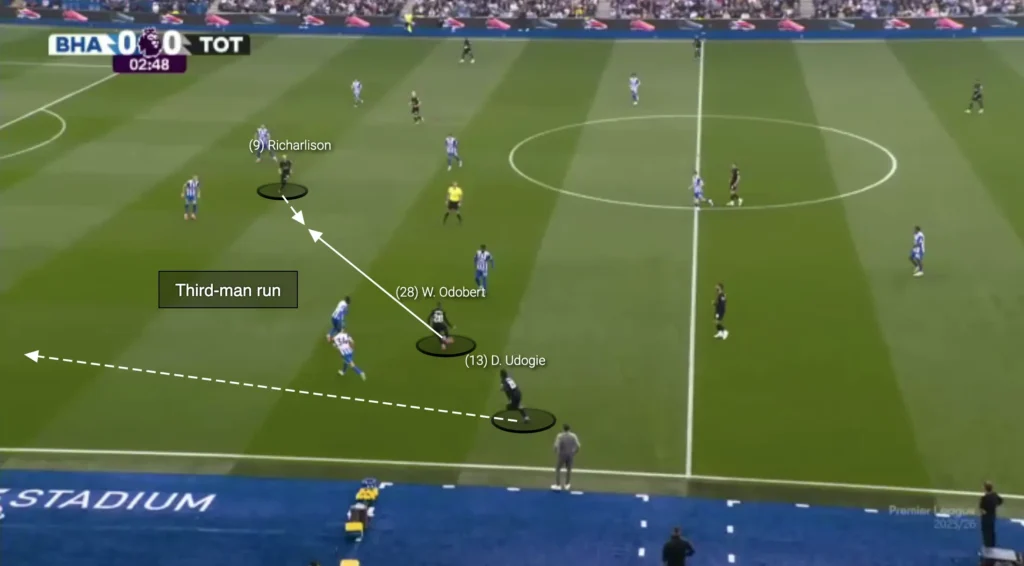

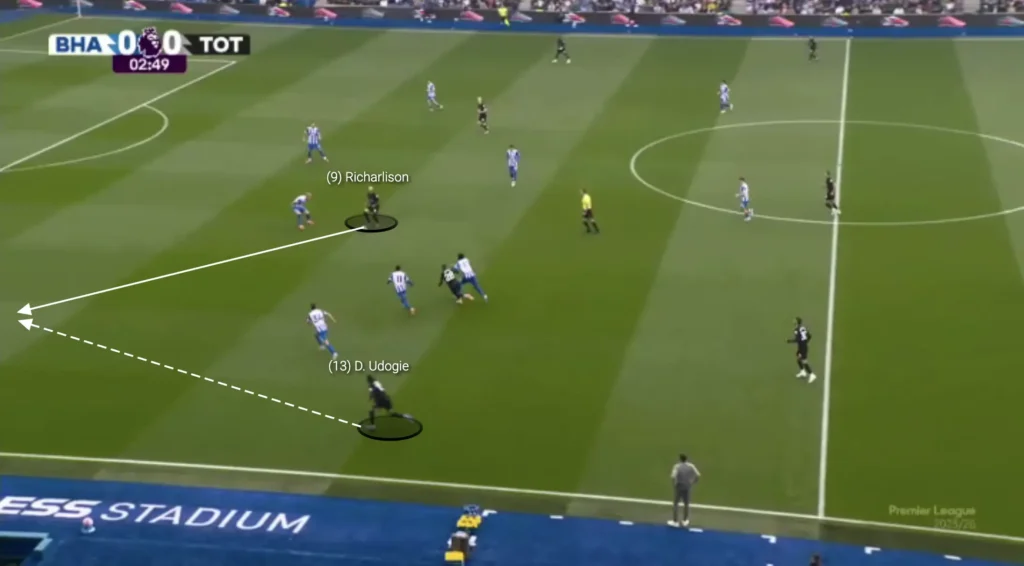

3. Third-Man Runs

Wide overloads often create ideal conditions for third-man runs — movements where the ball bypasses two players through a quick combination. Typically, a winger plays into an attacking midfielder or striker, who immediately lays it off to a third player — often a fullback — making a dynamic run into the space behind the defensive line. These third-man runs are essential for turning possession into penetration.

Defending Against Wide Overloads

From a defensive standpoint, wide overloads present serious challenges. If the defending team commits too many players to one side, they risk leaving central or far-side gaps. However, if they remain compact, the overload side can progress easily.

Teams often respond by:

- Using zonal compactness to prevent easy switches.

- Assigning cover shadows effectively to block interior lanes.

- Rotating the midfield line to shift collectively toward the ball while maintaining balance.

Some coaches prefer to invite the overload, anticipating the switch and setting pressing traps once the ball travels across — a common feature in well-drilled mid-block systems.

Conclusion

Wide overloads are a fundamental part of modern football — not just as a tool for maintaining possession, but as a mechanism for creating dynamic superiority and manipulating defensive structures.

They represent a delicate balance between structure and improvisation. The positions and rotations are rehearsed, but the timing, decisions, and technical execution depend on the players’ understanding of space and the collective rhythm of the team.

For coaches and analysts, studying how and when teams create these overloads offers valuable insight into their offensive identity. Whether used to dominate possession or trigger rapid switches, wide overloads remain one of the most effective and nuanced ways to unbalance an opponent in modern football.