Modern football demands that players process more information in less time than ever before. Defensive structures are compact, pressing triggers are aggressive, and space to receive the ball is constantly shrinking. The difference between merely coping with these pressures and dictating play often comes down to scanning—the act of gathering visual information before, during, and after possession.

Scanning is not limited to when a player is on the ball. It is a continuous process that begins before possession, continues while the ball travels, and influences decisions even off the ball. Whether anticipating pressure, recognizing passing lanes, or timing a run in behind, scanning provides the information that underpins intelligent action.

What Is Scanning?

At its core, scanning is looking away from the ball to collect cues about teammates, opponents, and spaces. But its value depends on three factors:

- Frequency – how often a player checks their surroundings.

- Timing – when the scan happens relative to the movement of the ball.

- Depth – what type of information is gathered (e.g., pressure, passing options, or free space).

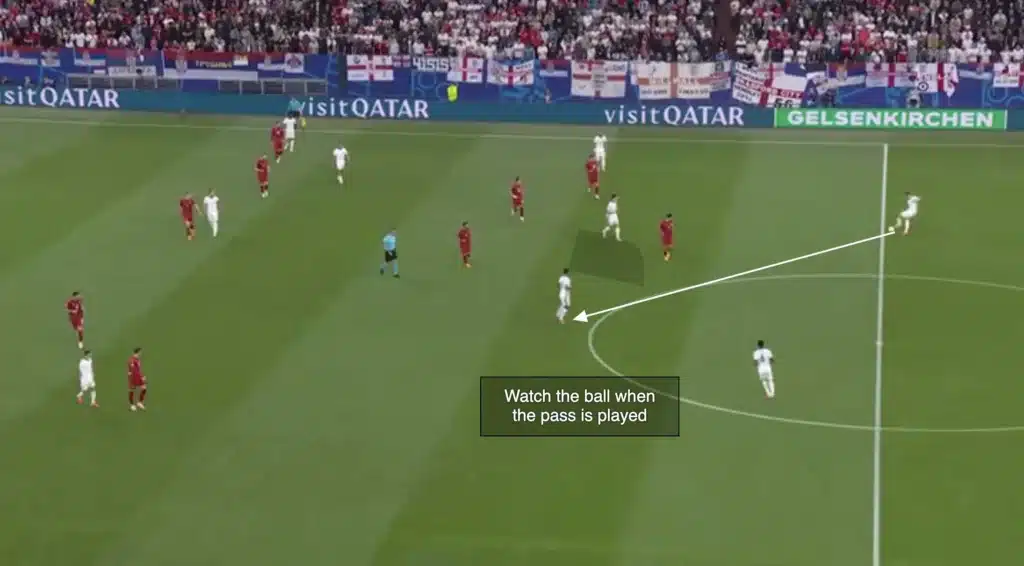

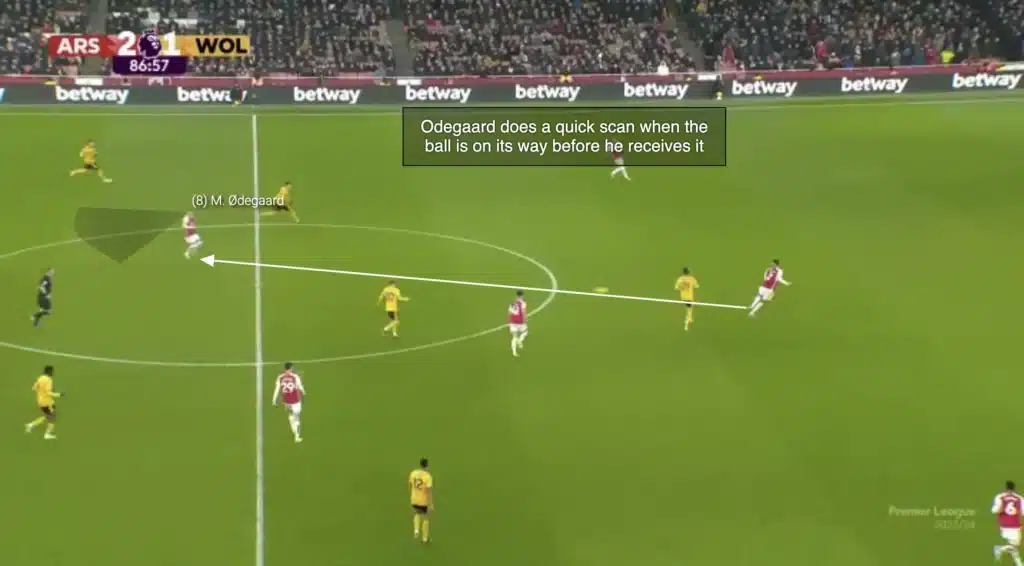

The most effective scanning moments occur while the ball is traveling—for example, from a center-back to a midfielder. In these fractions of a second, the receiver cannot influence the ball but has the time to update their mental map. Players who consistently scan during ball travel arrive more prepared, with a clear picture of their next action.

Scanning can also be done when the ball is in the air or between players’ touches when they are in possession of the ball.

Why Scanning Matters

1. Anticipation and Speed of Play

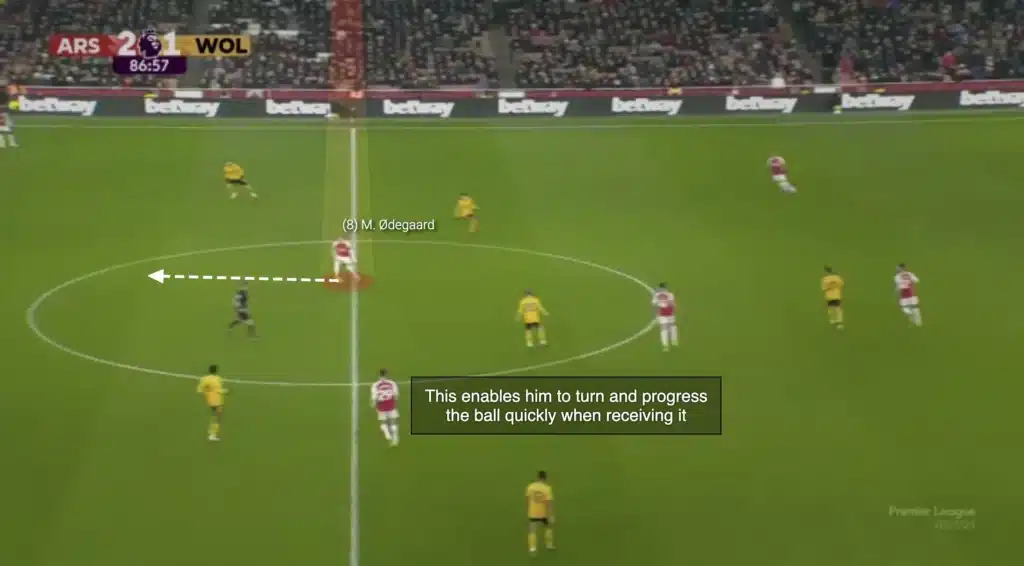

Scanning allows players to plan their next action before the ball arrives. By knowing their options in advance, they can receive on the half-turn, play forward in one touch, or disguise their intentions. This not only increases individual speed but also raises the overall tempo of the team.

2. Reducing Risk

Without scanning, players often receive blind and are caught by surprise pressure. Checking surroundings—especially while the ball is traveling—gives them the time to adjust body orientation, protect possession, and avoid costly turnovers in dangerous areas.

3. Creating Opportunities

Scanning does more than prevent mistakes; it creates advantages. Attackers can spot defensive gaps or time runs into blind spots, while defenders can anticipate passing lanes to intercept. Players who scan consistently are better placed to exploit openings the moment they appear.

Applied Example: Scanning in Build-Up

Imagine a defensive midfielder preparing to receive from a center-back:

- Before the pass: They scan to check opponent pressure and forward options.

- As the ball travels: A quick scan confirms whether the forward lane is still available or if a defender has closed it.

- Decision: With this information, they can receive open and play forward in one touch, or protect the ball and recycle if needed.

This entire sequence depends not only on technical skill but on when and how scanning occurs, especially in the moments while the ball is moving.

Scanning Beyond Possession

Scanning also applies off the ball:

- Defensively, players must scan to track runners, recognize shifting lines of pressure, and anticipate switches of play. A fullback, for instance, who fails to scan may be caught unaware by a winger drifting inside.

- In attack, forwards scan continuously to time runs and exploit defenders’ blind spots, not just when the ball is near.

By treating scanning as an all-phase behavior—not only “before receiving”—players develop the habit of constantly updating their awareness.

Training Scanning: Practical Methods

1. Small-Sided Games with Constraints

Conditions requiring players to identify external cues (colors, numbers) force scanning under pressure.

2. Rondos with Stimuli

In rondos, coaches can signal outside the playing area. Players must register the signal while maintaining possession, simulating ball-travel scanning.

3. Video Feedback

Reviewing clips highlights scanning frequency and timing, helping players understand where awareness broke down.

4. Progressive Drills

- Unopposed: Passing patterns with required scans at markers.

- Semi-opposed: Rondos with scanning challenges.

- Fully opposed: Match-like scenarios where successful actions depend on early awareness.

Common Pitfalls

- Ball Watching: Focusing only on the ball, ignoring surroundings.

- Late Scanning: Looking after receiving, leaving no time to adapt.

- Static Scanning: Checking once but failing to update as the ball travels.

Conclusion

Scanning is more than glancing around—it is the continuous act of building and updating a mental map of the game. The most effective players scan not only before receiving but especially while the ball is traveling, using those moments to prepare actions in advance.

It is a behavior that shapes both possession and non-possession phases, influencing anticipation, risk management, and attacking creativity. For coaches, it must be trained as a fundamental skill. For analysts, it provides a window into decision-making quality. For players, it is the key to slowing the game down and staying two steps ahead.

Football is a game of decisions. And every decision starts with what a player sees.