Football is not static. Even the most organized structures are constantly shifting, reacting, and adapting. Within this fluid environment, teams aim to create moments of imbalance — not just through positioning, but through movement and timing.

These moments are known as dynamic advantages.

A dynamic advantage is achieved when a team gains superiority through motion — by arriving into spaces faster, timing movements better, or manipulating the opponent’s reactions to create openings. It’s the advantage that appears for a split second — and disappears if not recognized or executed.

Static vs. Dynamic Advantages

While positional advantages depend on where players are located (for example, occupying the space between lines), dynamic advantages depend on when and how they move.

The same 4v4 can become a 4v3 if one attacker times his run perfectly or if a defender reacts half a second too late.

This temporal dimension — the exploitation of movement and rhythm — transforms equality into superiority. In elite football, those moments of movement and synchronization often separate control from chaos.

The Foundations of Dynamic Advantage

Dynamic advantages typically arise from three interacting elements:

1. Movement Timing

Players move not just to space, but into it at the right moment. A run made too early forces the ball carrier to delay; too late, and the gap has already closed. The coordination between passer, receiver, and space defines whether the action creates superiority or congestion.

2. Manipulation of Opponents

Before creating space, a team must move the opposition. This is achieved by drawing players out of position — through feints, circulation, or decoy movements. Once an opponent commits, the space behind or beside them becomes available for exploitation.

3. Synchronization

Dynamic advantages depend on collective timing, not individual runs. The moment one player moves, the others must adjust. When several players move in harmony — one dropping, one running, one supporting — defensive lines break down even without numerical superiority.

Common Patterns That Create Dynamic Advantages

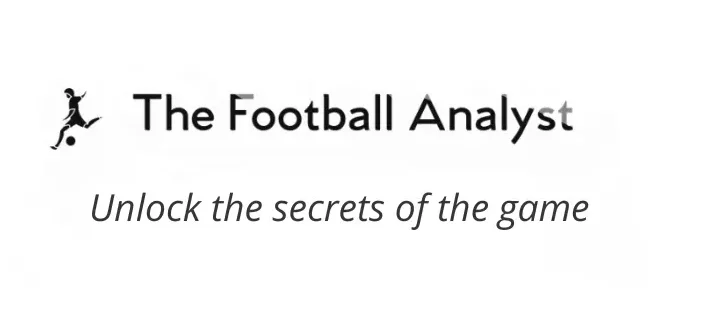

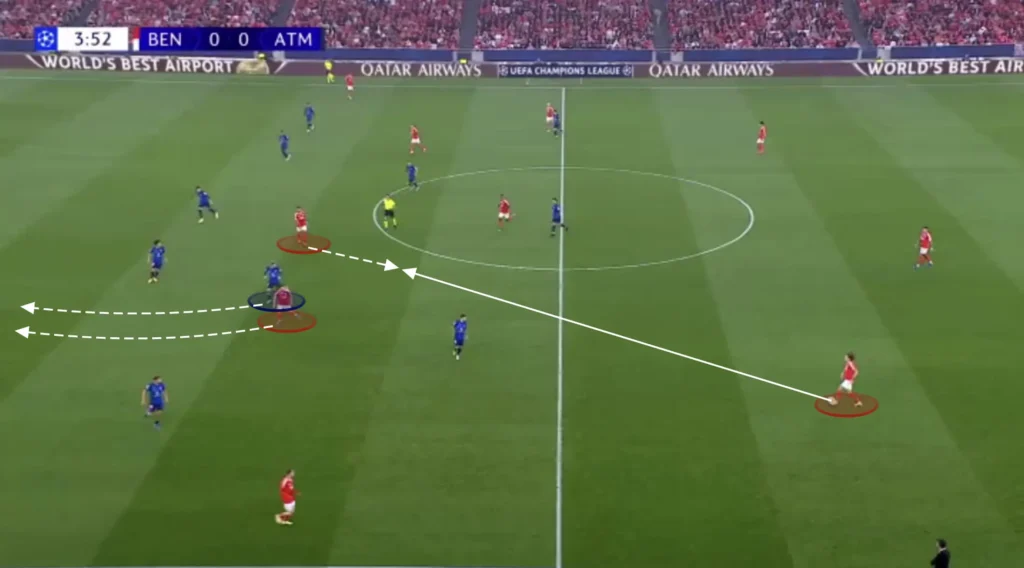

Third-Man Runs

A classic example: Player A passes to Player B, who lays it off for Player C arriving from depth. The advantage isn’t numerical — it’s dynamic. The timing of the third man’s run catches defenders facing the wrong way, unable to react in time.

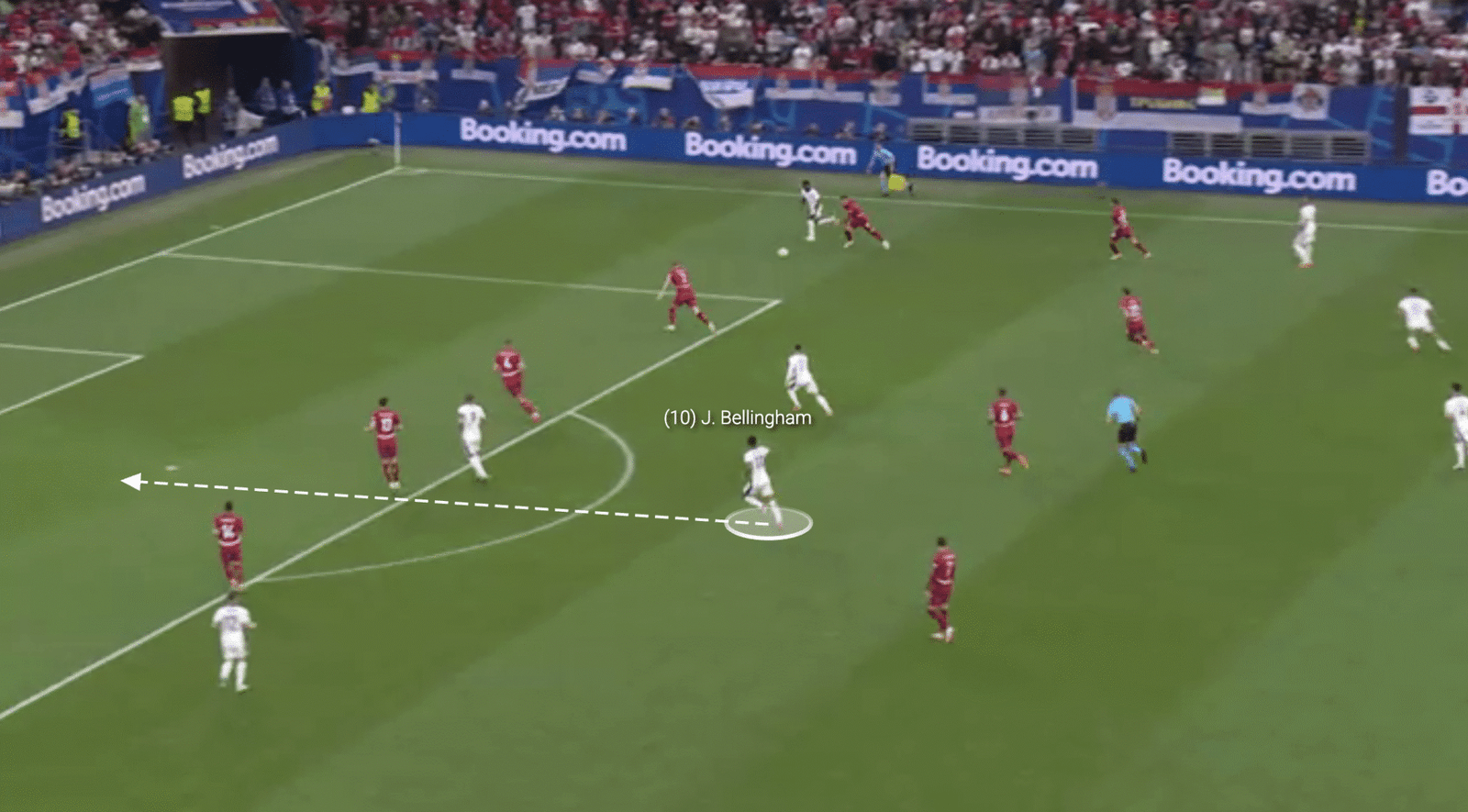

Rotations Between Lines

When players exchange zones — for instance, a winger drifting inside as the fullback overlaps — defenders lose their reference points. Even if they maintain their shape, their orientation changes, opening brief passing windows to progress play.

Diagonal Movements

Diagonal runs (from outside to inside or vice versa) disrupt defensive structures and create uncertainty. They allow players to arrive into the blindside of defenders, gaining momentum and positional advantage in one action.

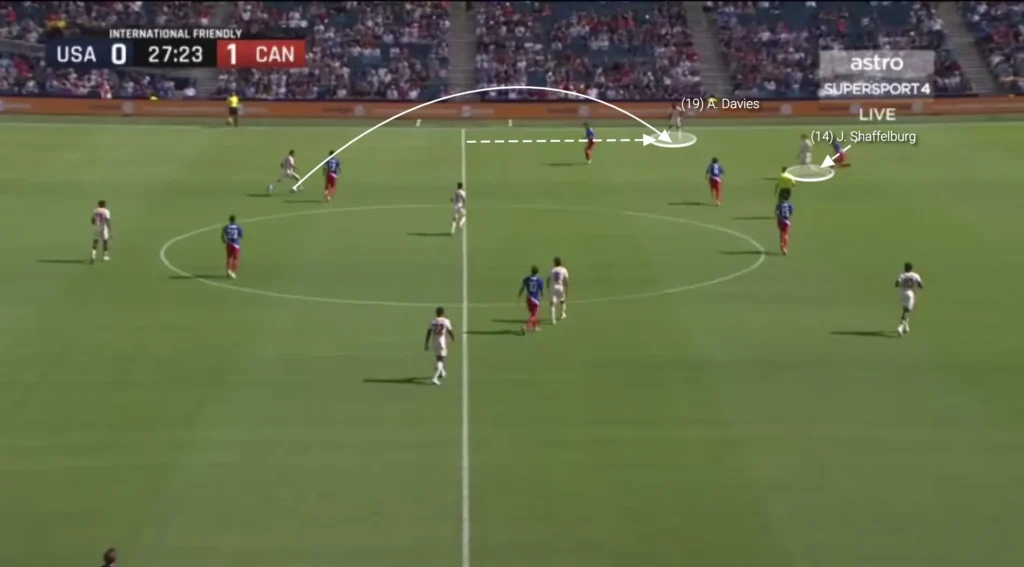

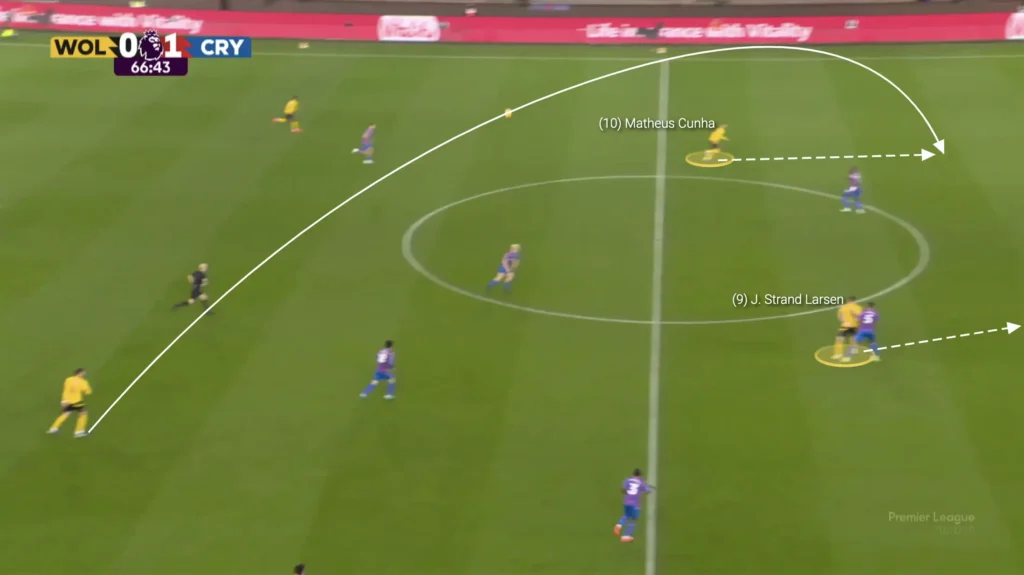

Counter-Movements

One of the most effective ways to manipulate space is through counter-movements. For instance, an attacker may first move short to draw the defender higher, then quickly accelerate into the vacated space behind. This change of direction forces hesitation, disrupts marking, and creates a brief but decisive dynamic window to receive in behind.

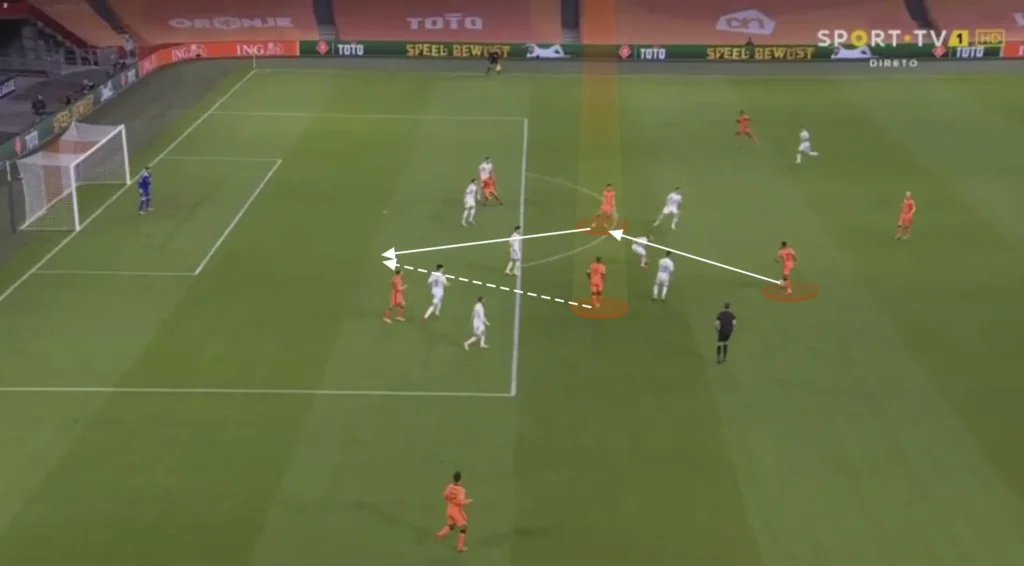

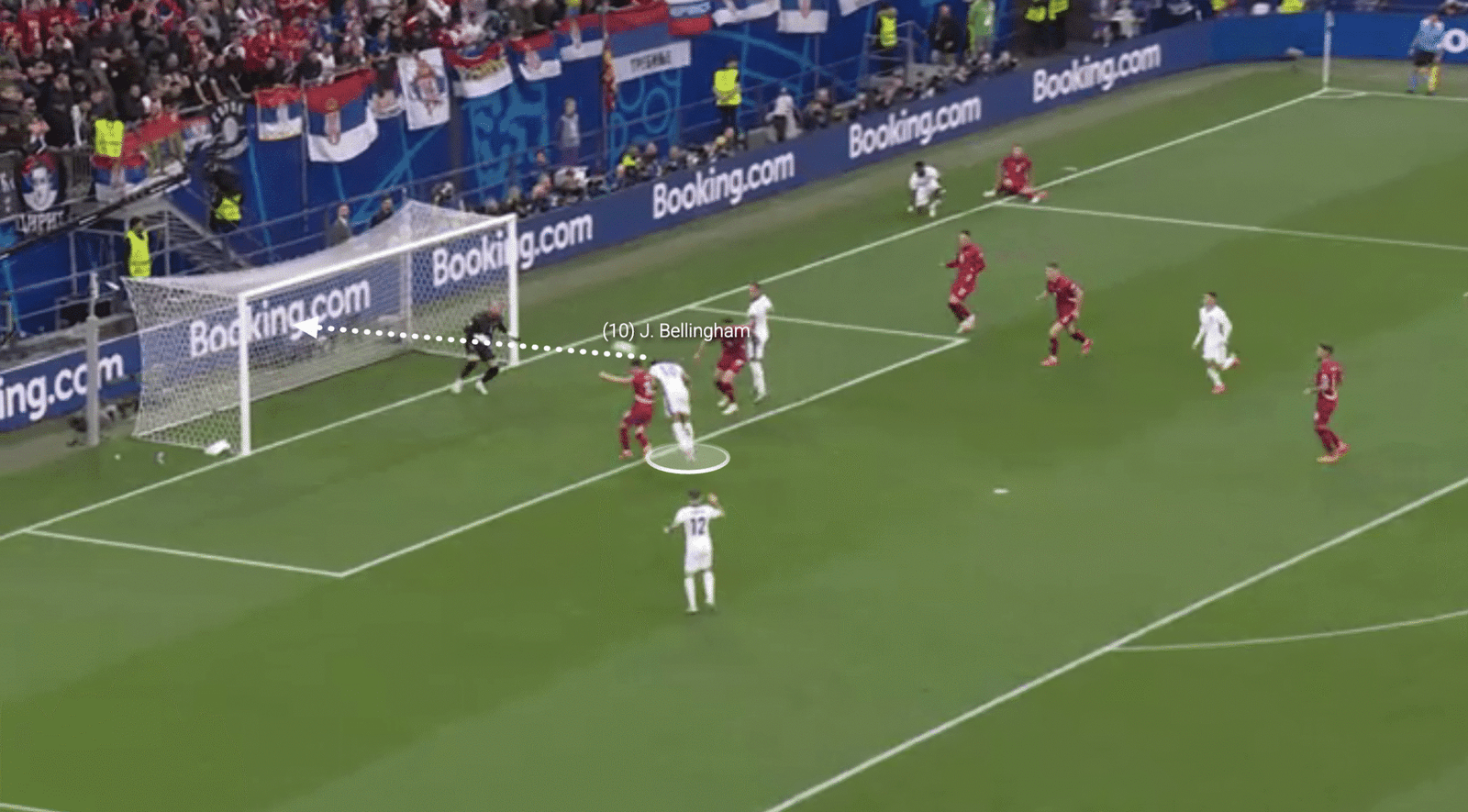

Delayed Runs from Deep

When midfielders or fullbacks arrive late into attacking areas, they exploit the moment when defenders are focused on the ball or marking active runners. These late arrivals often lead to free entries at the edge of the box or unmarked finishing positions.

Quick Positional Exchanges

Sudden switches between nearby players — such as a striker dropping short while the attacking midfielder runs beyond — force defenders to decide instantly whether to follow or hold. Either choice can be exploited.

Why Dynamic Advantages Matter

Modern defenses are increasingly compact, limiting space between lines and behind. Static positional play alone rarely breaks them down.

Dynamic advantages, however, create instability — they make defenders turn, chase, or hesitate.

Every slight misalignment counts:

- A center-back stepping up too early.

- A fullback caught mid-sprint as the ball switches side.

- A midfielder reacting a fraction late to a forward rotation.

Top teams train to recognize and exploit these temporary disorganizations. The objective isn’t constant movement, but purposeful movement — coordinated, timed, and linked to the collective intention of the play.

Dynamic Advantages in Transitions

Transitions — the moments immediately after losing or regaining possession — naturally produce dynamic advantages. The opposition is unbalanced, distances are inconsistent, and reference points are lost.

A well-timed forward run or quick vertical pass in these moments can bypass several defenders before they recover their structure.

However, the same logic applies defensively: teams that reorganize faster can neutralize the opponent’s dynamic advantage by controlling recovery timing and compactness.

From Chaos to Control

Dynamic advantages live in the thin line between structure and improvisation.

Too much rigidity, and the team becomes predictable. Too much freedom, and movements lose coordination.

The best sides master the balance — maintaining a collective framework while allowing individual initiative within it.

They understand that superiority isn’t just created by numbers, but by moments — when time, space, and movement converge.

Conclusion

Dynamic advantages define the rhythm of elite football.

They emerge through coordinated movement, intelligent timing, and the ability to manipulate the opponent’s reactions.

While positional play provides the structure, it’s the dynamic actions that unlock defenses and turn control into penetration.

In a game decided by seconds and meters, dynamic superiority is the invisible edge — the art of arriving at the right place, at the right time, in the right way.