For years, long throw-ins were seen as a relic of an older football era — a brute-force tool that clashed with modern ideals of possession, structure, and control. But in the 2024–25 season, that perception has changed dramatically. The long, flat torpedo throw is back — and it’s more effective than ever.

Data from this season shows that 20m+ throws into the box have more than doubled, rising from 1.52 to 3.44 per match, and they’re now producing over twice the xG of any previous year on record. The numbers tell a clear story: what was once dismissed as a low-percentage tactic has re-emerged as one of football’s most direct and disruptive attacking tools.

The Tactical Function of a Long Throw

At its core, the long throw-in serves the same purpose as a cross or corner — to deliver the ball into a crowded penalty area where second balls, deflections, and chaos can generate goal-scoring opportunities.

However, what makes the long throw unique is its combination of precision and unpredictability.

Unlike a corner, which comes from a fixed angle and height, a throw-in can vary in trajectory, spin, and delivery point. The flat, fast throw — often traveling more than 20 meters — arrives in the box with speed, forcing defenders to make quick, instinctive decisions. For the attacking side, this creates a compressed, chaotic environment that favors aggression and timing over technical precision.

Why Long Throws Are Making a Comeback

There are several tactical and structural reasons behind the resurgence of long throw-ins:

1. Compact Defensive Blocks Create Fewer Open-Play Chances

With most teams defending in well-drilled compact blocks, creating high-quality chances from open play has become increasingly difficult. Long throws bypass structured defenses altogether, delivering the ball directly into the most dangerous zone — the penalty area.

2. Modern Data Analysis Values Efficiency

Clubs like Brentford and Midtjylland were early adopters of data-driven set-piece strategies, recognizing that throw-ins could produce consistent xG returns. As tracking data evolved, analysts began to quantify not just goals but expected threat — showing that long throws can rival corners in terms of overall danger.

3. Specialist Coaching and Technique

Throw-in coaching, once unheard of, is now part of elite preparation. Players are trained not just to throw far, but to throw flat — with minimal arc and maximum speed. The goal is a low, fast trajectory that lands near the six-yard box before defenders can reset.

Brentford’s Michael Kayode has become a master of this art, already responsible for five of the twenty longest throws in Europe this season.

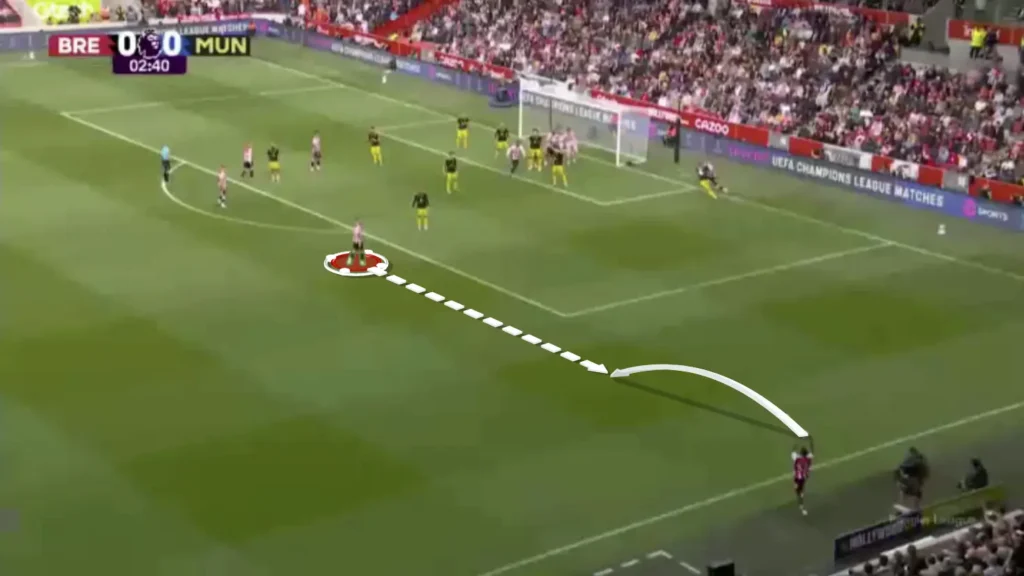

The Mechanics: How Teams Structure Long Throw Situations

A long throw is not just a physical act — it’s a coordinated routine involving timing, positioning, and role distribution. Effective teams use structured patterns to maximize their chance of creating danger.

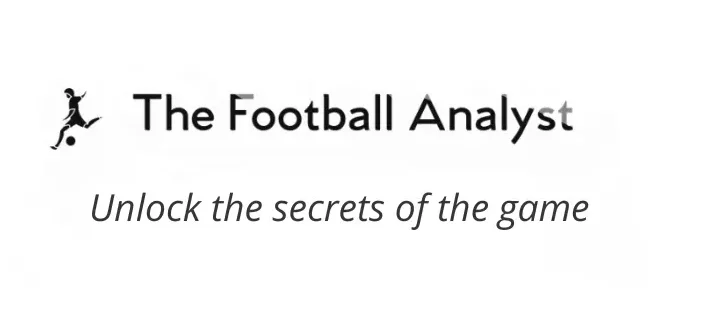

Near-Post Flicks

A group of attackers target the near post, where one or two players attempt to flick the ball on across the goalmouth. This creates confusion for defenders and forces the goalkeeper to stay reactive rather than proactive.

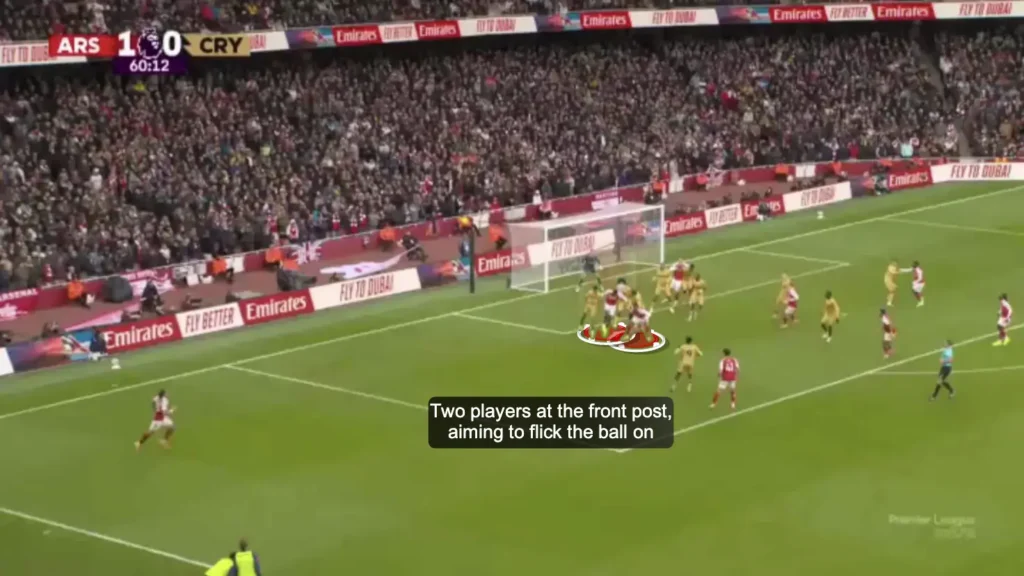

Back-Post Attacks

While the near-post players occupy attention, another group positions further back at the far post, ready to attack flick-ons, rebounds, or loose balls. This separation between near and far creates a dynamic, layered threat.

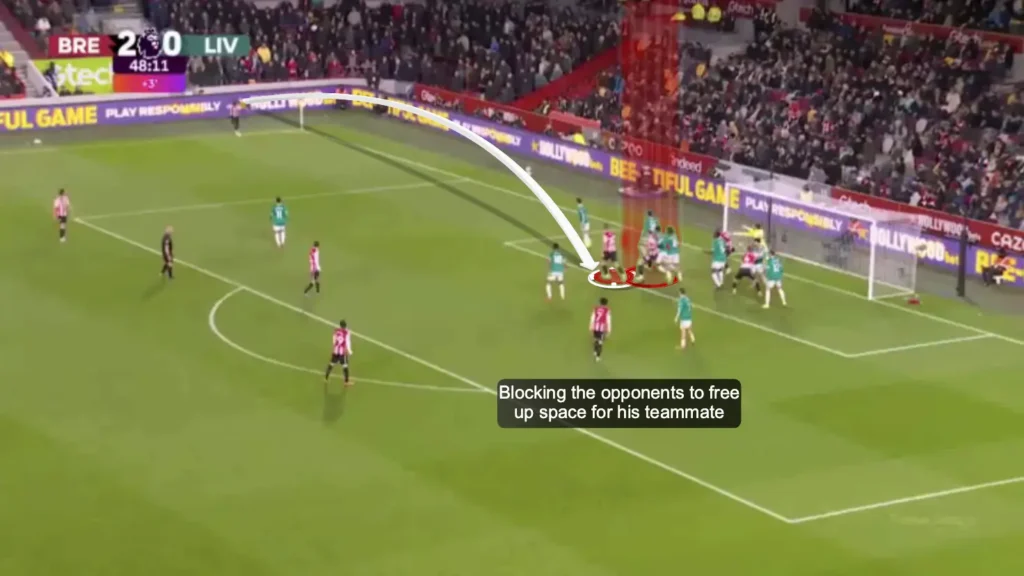

Screens and Blockers

Attackers will often use blocking runs to impede defenders’ movement or delay their jumps. These screens, while subtle, can make the difference between a clean clearance and a defensive scramble.

Second-Ball Structure

Teams like Brentford are particularly effective at recovering second balls from long throws. Players are positioned just outside the box to win loose balls and immediately recycle possession into another cross or shot.

The Hidden Benefits: Psychological and Positional Pressure

Beyond pure chance creation, long throws exert a psychological toll on defenders. They force opponents to retreat deep, crowd their own box, and defend multiple consecutive aerial duels. Over the course of a match, this repeated pressure can fatigue defenders and push the defensive line back several meters — giving the attacking team more territory.

Long throws also provide positional pressure. A team can move its entire block high up the pitch, using the throw as a trigger for sustained attacking pressure. Even if the initial throw doesn’t lead to a goal, the resulting possession often pins the opponent deep in their own half.

Adapting to Modern Defending

While some teams choose to defend long throws zonally, others opt for man-marking in the box. The most effective attacking routines exploit whichever defensive method is used:

- Against zonal defenses, the aim is to flood specific zones with multiple attackers, overloading the main aerial duel.

- Against man-marking systems, movement and blocking runs are used to create separation and attack the space behind.

Modern long-throw teams also mix in short throws and fake setups to remain unpredictable. If defenders drop too deep expecting a long launch, the thrower can play short to a nearby teammate, quickly changing the angle and creating space for a cross.

Why It Works in the Modern Game

In an era where teams are becoming increasingly structured, rehearsed, and organized, the long throw thrives precisely because it breaks structure.

It introduces randomness into a game that has become systematically controlled — and in football, controlled chaos can be one of the most valuable tools.

Where a patient possession sequence might create a 0.05 xG chance, a single throw-in can instantly generate a 0.15–0.20 xG situation with minimal build-up. For analysts and coaches seeking marginal gains, those numbers are impossible to ignore.

Conclusion

The long throw-in has evolved from an old-school weapon into a modern tactical asset.

No longer dismissed as primitive, it’s now a data-backed, carefully designed tool that brings both efficiency and unpredictability to attacking play.

Whether used by Brentford’s specialists or integrated into broader set-piece systems across Europe, the long throw-in represents a clear trend: football’s smartest teams are learning that sometimes, the most direct path to goal is also the most effective.

All images and tactical visuals in this article were created using Once Sport—one of the most advanced and user-friendly platforms for annotating footage, visualizing movements, and producing high-quality analysis clips. As a reader of The Football Analyst, you can enjoy 10% off plus one month free with code TFA10 at checkout.