Football is often described as a game of space — how to create it, control it, and exploit it. For years, this idea has been dominated by one framework: positional play (juego de posición). Yet, while positional play organizes the pitch through zones and spacing, a new interpretation is emerging from South America and southern Europe — one that defines structure through relationships, not positions. This approach is called relationism, and it is transforming how coaches, analysts, and scouts understand collective behavior on the pitch.

Beyond Structure: What Relationism Really Is

Where positional play seeks control through geometry, relationism finds it through connection. Instead of building attacks from a fixed shape, it builds them from proximity, interaction, and intuition.

In positional football, the pitch is divided into zones that players must occupy at the right times to maintain spacing and balance — the goal is to stretch the opponent.

In relationism, players stay closer together, creating short distances to connect with one another. The goal is not to stretch, but to combine — to overwhelm opponents through coordinated movement and passing rhythm.

This makes relational football appear freer, more spontaneous, and less structured — yet underneath that freedom lies a strong internal order. The structure emerges from the relationships themselves, rather than being imposed on them.

It is less about “where should I stand?” and more about “how can I help the next action?”

The Core Values of the Relational Model

The relational model is guided by a few key principles that shape how players behave collectively:

- Proximity: Staying close to teammates ensures immediate support, tight combinations, and overloads in key areas. It allows for faster circulation and instant counterpressing when possession is lost.

- Adaptability: The team’s shape is fluid and constantly shifting based on where the ball and teammates are. Players interpret space dynamically, not mechanically.

- Interaction: Every action is relational — players think in pairs and trios, creating collective rhythm through short sequences, wall passes, and rotations.

In essence, the team’s structure emerges from these relationships. Position is not predetermined; it is co-created through movement, communication, and awareness.

The Logic of Connection

Relationist play relies on a few key behaviors that shape its rhythm and form.

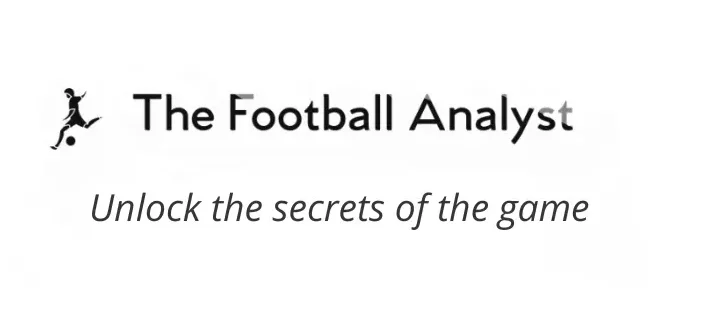

1. Constant Movement – Toco y Me Voy

At the heart of relationism lies toco y me voy — “I play and I go.” It’s the immediate movement that follows the pass. Unlike in positional play, where players hold zones to preserve structure, relationist players are constantly in motion, creating new passing lanes and disrupting defensive stability.

This simple principle — pass and move — is what gives relationist football its fluidity. The play never pauses to reset shape; it keeps breathing.

2. Collective Combination – Tabelas

Movement alone isn’t enough without connection. The tabela — wall passes or the classic “one-two” — embodies relationism’s relational essence. Every pass is an invitation for interaction, a dialogue between teammates.

Rather than mechanical rehearsals of positional triangles, tabelas form naturally, often in tight areas, allowing players to escape pressure and progress through pure cooperation.

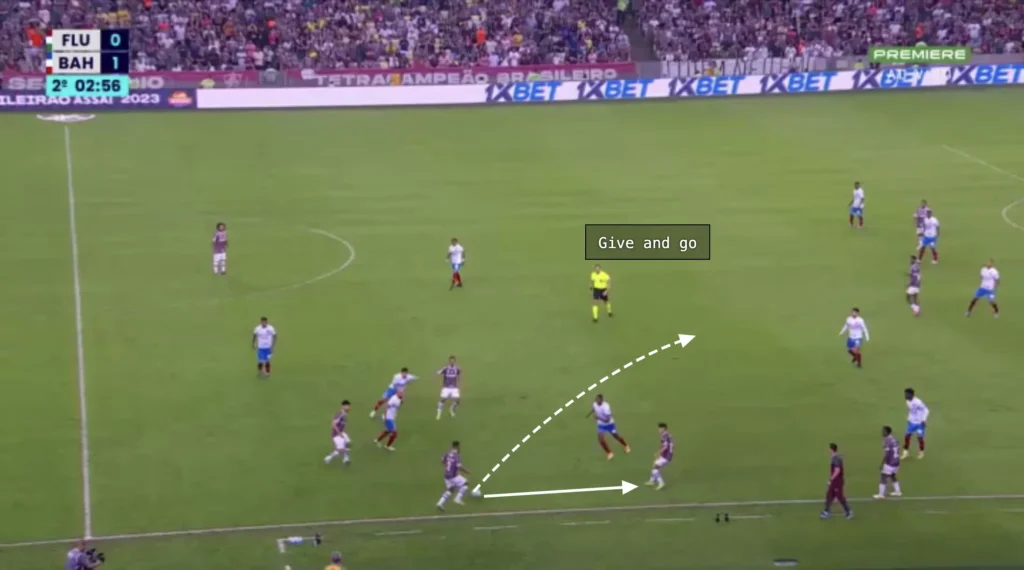

3. Diagonal Support – Escadinhas and Corta Luz

While positional systems emphasize vertical and horizontal spacing, relationism prefers diagonals. Escadinhas (literally “staircases”) describe how players position themselves diagonally ahead or behind one another, allowing progression up the field through quick, relational links.

The corta luz (“cut the light”) complements this — the dummy, the feint, the act of deception that disorients defenders and lets the ball flow to the next receiver. In relational football, these movements are not isolated skills but coordinated acts of collective rhythm.

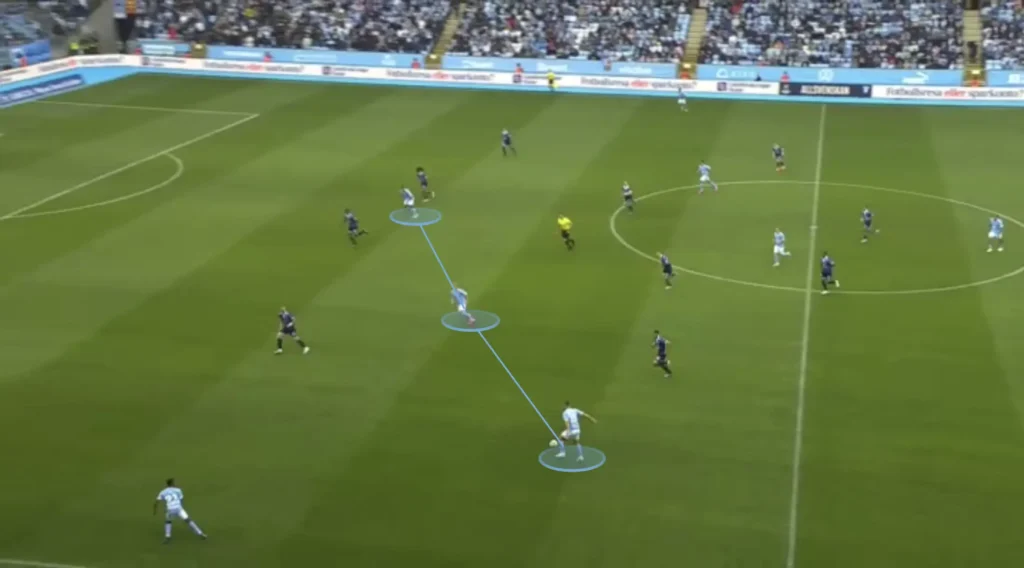

Tilting the Field

If positional play is about symmetry, relationism is about tilt. Players gather around the ball, usually on one flank and not in the center, compressing space to ensure close distances between teammates. This creates density, allowing the team to maintain possession through short combinations and immediate counter-pressing if the ball is lost.

By tilting toward one side, relationist teams — like Fernando Diniz’s Fluminense — create a kind of collective gravity. The ball attracts bodies, the structure bends, and new angles appear.

Critically, this proximity doesn’t just aid attacking play; it also functions as rest-defence. Instead of leaving a fixed 2–3 or 3–2 behind the ball, the entire team remains compact and ready to recover immediately through relational closeness.

Relationism vs. Positional Play: The Philosophical Divide

Both models seek to control the game — but in different ways.

- Positional Play values order before the action. Each player occupies a fixed role to preserve width, depth, and balance.

- Relationism values order through the action. Each player adapts in real time, shaping and reshaping the structure based on teammates’ movements.

One system is geometric, the other relational.

One prioritizes zones, the other prioritizes relationships.

The beauty of relationism lies in its human quality. It trusts players to interpret, to respond, and to create — not just to execute.

The Strengths and Challenges of Relationism

Strengths

- Encourages creativity and improvisation

- Enhances collective understanding and connection

- Produces fluid attacking movements that are difficult to predict

- Adapts naturally to changing match contexts

Challenges

- Requires exceptional player intelligence and chemistry

- Can lead to defensive instability if spacing collapses

- Difficult to implement without long-term cohesion or training time

Where positional play is a system, relationism is a language. All eleven players must speak it fluently — otherwise, it breaks down.

Blending Relationism and Positional Play

While relationism and positional play are often presented as opposites, in practice, the best modern teams draw from both frameworks. The game’s evolution has blurred the line between them — it’s no longer about choosing one philosophy over the other, but about understanding when and where each is most effective.

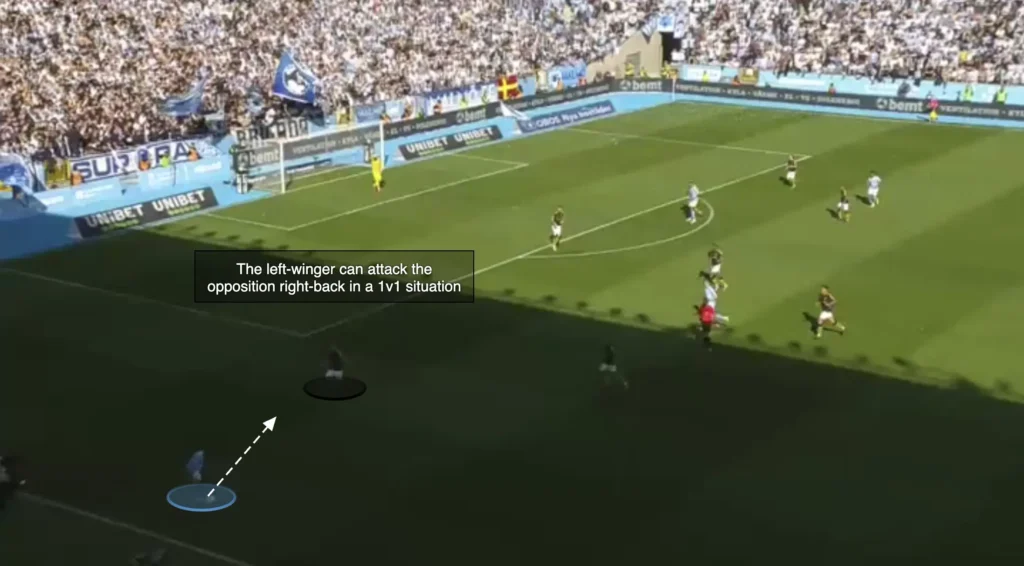

A key example of this synthesis is the overload-to-isolate tactic. In this approach, a team intentionally overloads one side of the pitch — drawing the opposition’s defensive structure toward the ball. Within that overloaded zone, relationist principles come alive: players operate in tight proximity, combine through one-twos, rotations, and diagonal movements (tabelas, escadinhas), manipulating defenders through relationships and rhythm.

Once the opponent’s shape has been pulled across, the team switches play quickly to the far side — where a wide player finds themselves isolated 1v1 in space. This second phase represents positional play logic, exploiting the geometry and balance created by the initial relational overload.

Teams like Hansi Flick’s FC Barcelona and Luis Enrique’s PSG have mastered this hybridization. They blend relational creativity in local zones with positional discipline across the overall structure, ensuring both fluidity and stability.

The result is a model that mirrors the complexity of modern football itself — a dynamic equilibrium between improvisation and organization, between rhythm and structure.

Conclusion

Relationism is not a rejection of positional play — it’s an evolution of it. Where positional play defines order before the pass, relationism defines order through the pass.

Its rhythm is human, its structure organic. Toco y me voy, tabelas, escadinhas, and tilting are not isolated concepts, but the grammar of collective connection.

In essence, relationism transforms football into something closer to conversation than choreography — a living dialogue among players who think together, move together, and trust the rhythm of relation.