For decades, coaches have been preoccupied with the idea of playing forward. The concept seems so ingrained in football that it’s rarely questioned: move the ball up the pitch, break lines, get closer to goal. But in a game where space is scarce and time even more so, the route forward isn’t always straight ahead. In fact, it’s often not.

This is where the concept of diagonality in possession enters the conversation — not as a new trend or fashionable buzzword, but as a timeless tactical tool that reshapes how teams manipulate space, disguise intentions, and structure their positional play.

Why Straight Isn’t Always Best

Vertical passes are praised for their directness, for the speed with which they carry the ball into threatening areas. But their benefits come with a cost. Vertical play often travels into pressure. It limits the receiver’s field of vision and demands quick body adjustments to escape surrounding defenders. At the other extreme, horizontal passes may offer safety, but they rarely disorganize an opponent. They move the ball without necessarily moving the opposition.

Diagonal passing, meanwhile, offers a more nuanced form of progression. It merges vertical ambition with horizontal control. The ball travels forward and sideways, opening angles, shifting blocks, and allowing receivers to face play with more natural body orientation. In short, diagonality doesn’t just move the ball — it moves the game.

Disguising Intent, Expanding Perception

There’s an element of deception in a well-weighted diagonal pass. From the perspective of the defender, it’s harder to anticipate — harder to read both the passer’s intention and the receiver’s next move. The pass may bypass two lines at once or land in pockets of space just beyond the reach of a pressing midfielder. The diagonal angle disrupts standard pressing triggers that are calibrated to respond to forward or lateral motion.

On the other side of the ball, the receiver benefits too. A diagonal pass often arrives in a player’s natural field of vision, allowing for quicker control and decision-making. There’s no need to turn sharply or reposition awkwardly. The receiver can scan the next action as the ball arrives — whether it’s a carry, a switch, or a layoff. That fractional advantage can decide whether a team breaks through or gets boxed in.

Creating Multi-Directional Threats

One of the most valuable traits of a diagonal pattern is that it keeps multiple attacking paths alive. Receive diagonally, and you can play back down the same path, switch to the opposite flank, or punch vertically through a new channel. Contrast that with a flat horizontal pass to the wing, where continuation often means working away from goal, and redirection requires additional time and touches.

Diagonal passes and movements expand the possibilities. They create what we might call positional elasticity — the ability to stretch, compress, and reshape the opposition’s block without losing the connection to goal. Instead of simply going through or around, teams can zig-zag their way between pressure points, constantly realigning their angles to preserve forward momentum without unnecessary risk.

Structure Breeds Diagonality

Diagonal patterns don’t emerge randomly. They depend on structure. The growing popularity of formations that create staggered lines — 3-2, 2-3, or inverted fullback setups — reflect this need for layered positioning. These shapes naturally generate the passing lanes and support angles required to play diagonally.

Whether it’s a pivot stepping into the channel between two forwards or a winger dropping inside to connect through the half-space, diagonal options require deliberate spacing. These small positional shifts have big consequences. They make the defense defend in curves, not lines. They force the opposition to scan both depth and width — a constant recalibration that eventually creates cracks.

Diagonal Carries and Rotations

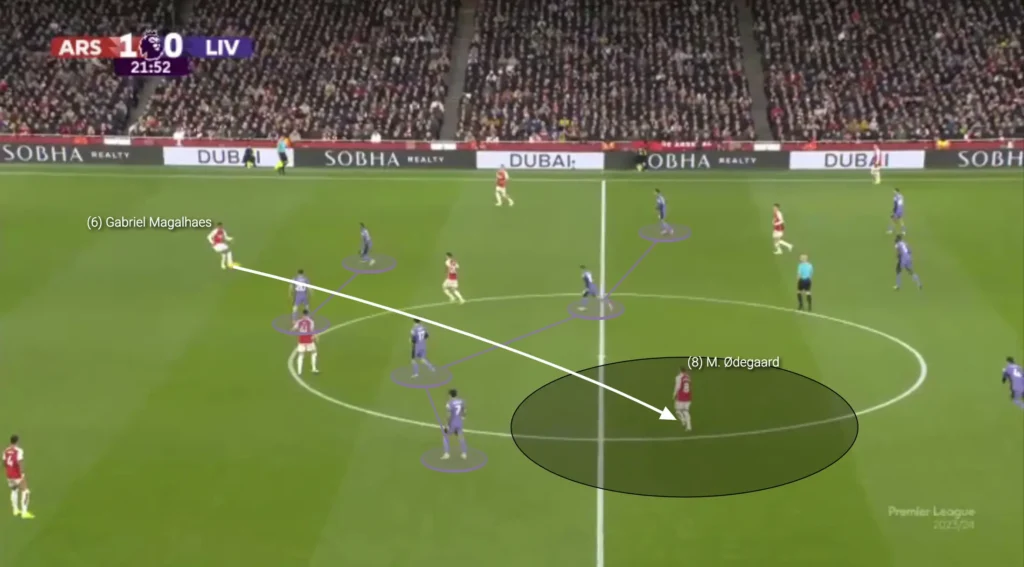

It’s not just about the pass. Ball carriers who drive diagonally can force defenders into uncomfortable decisions: step forward and risk leaving space behind, or stay passive and let the attacker advance. These carries often tilt defensive lines, opening the opposite side or inviting third-man combinations.

In this situation, for example, the Real Madrid center-back takes the ball forward diagonally, shifting the opposition structure and opening space to find a player in between the lines. This player can then lay the ball off to a forward-facing midfielder, who can attack the opposition backline.

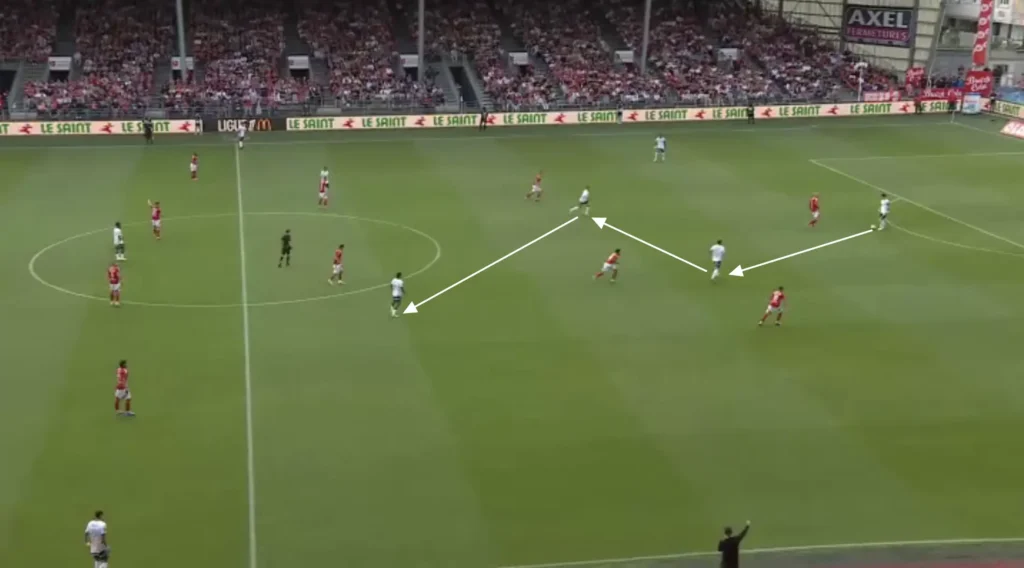

Similarly, off-ball movements along diagonal paths — a midfielder peeling away at an angle, a fullback underlapping into the interior — create subtle dislocations in defensive shapes. These actions don’t just support the next pass; they prepare the one after.

In this situation, for example, the Brighton right-back inverts by making a diagonal run into the midfield, which forces the opposition wingers to follow and cover the run. This opens the passing lane from the center-back to the winger and enables Brighton to progress the ball forward.

When Control Fails, Diagonality Remains

Not every team can dominate the center like peak Barcelona or today’s top possession sides. In many matches, control is temporary — a phase rather than a constant. But even when central dominance fades, diagonality remains a weapon. It offers teams a way to recover control: to exit pressure, to re-enter the middle from wide areas, or to restart circulation without losing intent.

Teams like Bayer Leverkusen under Xabi Alonso or PSG under Luis Enrique have embraced these ideas. Their positional play relies on diagonal connections from deep midfielders to inverted wingers, from center-backs into zone 14. It’s not about brute force or tempo alone — it’s about breaking rhythm, warping angles, and resetting the game on their own terms.

Conclusion: Diagonality as Possession Intelligence

Diagonality is not a philosophy. It’s a language. A way of shaping possession that values ambiguity, direction, and control all at once. In a sport obsessed with speed and intensity, it offers a subtler path — one that favors positioning, perception, and precision.

Possession for its own sake is no longer enough. The game demands possession that penetrates, that adapts, and that disorients. Diagonality gives teams the tools to do just that — by moving not just the ball, but the game itself.

Very good and inteligence article